In specific locales, young women make more than their male counterparts, earning 120% of men’s salaries, in some cases. Why is the pay gap flipped in certain areas?

West Virginia is a US state commonly cited for its coal mines and country roads – not for its place in the pay-gap conversation. But according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of US Census data, the metropolitan area of Morgantown – the state’s third largest city, home to West Virginia University – is one of only a few places in the nation where women out-earn their male counterparts.

In this area, the median salary of full-time female workers younger than 30 is 14% more than the median salary of men in the same group. In fact, the Appalachian city is second – just behind Wenatchee, in the state of Washington – on a top-10 list of metro areas where women younger than 30 come out on top comparatively.

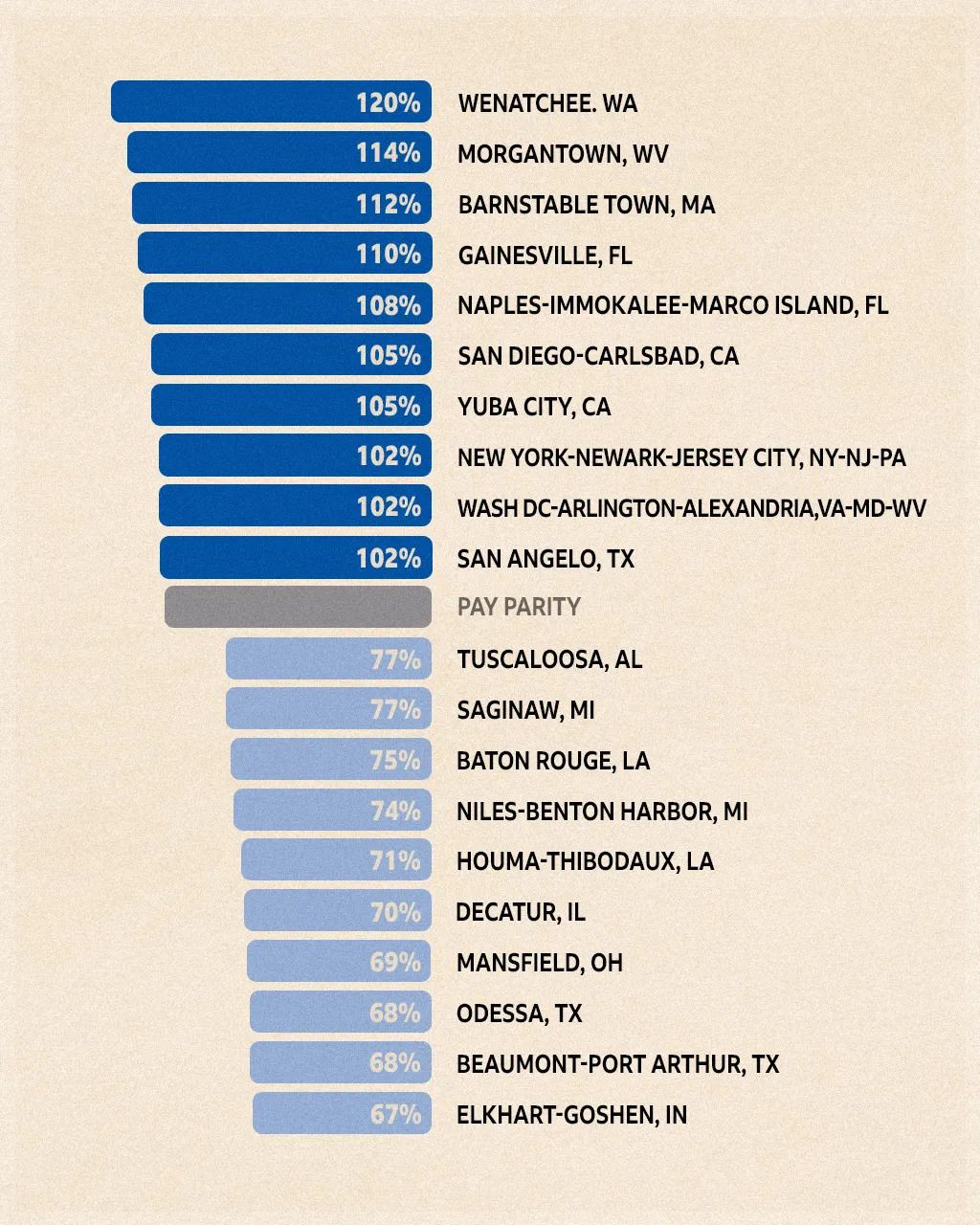

Nationally, the gender wage gap persists; on average, US women earn 82 cents for every dollar their male peers are paid. But in 22 of the 250 metros examined in the analysis, women’s salaries are on par or better. Why do women out-earn men in highly specific areas of the US – and do promising figures in certain areas mean the wage gap could be slowly closing?

Education and industry

There are some patterns that help explain these findings, says Richard Fry, senior researcher with Pew, who authored the report.

First, education is a factor. The places where women have parity or out-earn men – mostly cities along the country’s east and west coasts – have a higher percentage of young women with degrees, explains Fry. “In metros where young women have a bigger advantage educationally, the pay gap tends to be smaller,” he says. “Completion of bachelor’s degrees tends to boost earnings, and the pay gap tends to narrow down.”

The US cities where women younger than 30 are earning both the most and least, compared to their male counterparts

The US cities where women younger than 30 are earning both the most and least, compared to their male counterparts

This component may at least partially explain why some specific cities in Florida and West Virginia make the top-10 list, despite their respective statewide average wage gaps of 15% and 26%. “Morgantown is a university town,” says Fry, “and so is Gainesville, Florida … among the 22 metros where there’s either parity or better, many are home to large universities.”

Those towns may have an outsize number of higher-paying jobs on offer. Plus, women who stick around in these metro areas after graduation stand to be paid better, thanks to the “educational advantage”, says Fry.

Education is also likely at least partially what propels Wenatchee, Washington to the very top of the list. The median annual salary of women there is 120% that of young men. “In Washington, 60% of women, I believe, have a bachelor’s degree,” says Fry. “So, you're talking about a really well-educated young women's workforce in Washington.”

Another factor influencing the wage gap is the type of jobs and industries that dominate certain geographic areas. The second-largest employer in Wenatchee is the metro’s school district; in the US, women fill more than three-quarters of education jobs. Women’s share of manufacturing jobs, on the other hand, is below 30%. In a number of metro areas where the wage gap is largest – including Saginaw, Michigan; Decatur, Illinois; and Mansfield, Ohio – manufacturers are among the top employers.

In metros where young women have a bigger advantage educationally, the pay gap tends to be smaller

“The metro with the greatest pay disparity is Elkhart-Goshen, Indiana, where young women only earned 67% of their male peers,” says Fry. “That’s kind of known as the ‘RV [motorhome] capital of the world’.” In fact, more than 80% of global RV production happens in that region of northern Indiana, near the Michigan border. “There’s a lot of manufacturing going on, and that can have consequences for how well young women do compared to young men.”

The motherhood factor

When – or if – women choose to have children can play into a geographic area’s wage gap. Throughout the country – and across the globe, in countries including the UK – women suffer from a ‘motherhood penalty’ that widens the wage gap; once women become mothers, they earn even less relative to men (meanwhile, men see their earnings go up when they become parents). By some estimates, mothers make only 70 cents for every dollar fathers do.

Motherhood is indeed a major driving factor of these wage gap statistics, says Alexandra Killewald, a professor of sociology at Harvard University. “The estimated penalty to your hourly wage for being a mom is in the neighborhood of 10 or so percent, compared to what we would have expected if you had continued without having children,” she says.

So, in regions where women become mothers earlier, the pay gap suffers, too. In Elkhart County, Indiana – home to the greatest pay disparity – the average age of a first-time mother is nearly three years younger than the national average of 26.3. In places where the average maternal age at first birth is lower, the wage gap is wider – and the inverse is also true. In the New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania metro areas, for instance, women earn 102% of what men do. In Manhattan, located within this geographical cohort, the average age at first birth is more than 31.

Areas home to large educational institutions, like West Virginia

University in Morgantown, tend to have smaller pay gaps for young women

Areas home to large educational institutions, like West Virginia

University in Morgantown, tend to have smaller pay gaps for young women

“Over time, we've seen increasing delays in first birth, and some decline in the number of children women have,” says Killewald. “That means more women are childless for longer, and they spend more of their working lives having not yet had a child.” Thus, she explains, they’re able to stay in the workforce without interruption, with their earnings keeping pace with their male counterparts.

But roughly 85% of American women, regardless of where they live, will eventually have a child, says Killewald. In terms of wage parity, things have a tendency to go downhill once their children are born.

A harbinger of progress – or not?

Although this new data provides good signals for women in many locations, there’s a caveat: the Pew report only examines the data of women ages 16 to 29. Historical patterns say that after 30, the gap will begin to widen.

Fry cites comparable data that may help paint a picture of the future. “Back in 2000, young women under 30 were making 88 cents on the dollar relative to their young male peers.” Another study of that group in 2019 found them “ages 35 to 48, and making 80 cents compared to their same-aged male peers. If today’s young women follow a similar pattern to earlier groups, the gap is likely to widen”.

But that’s just a prediction based on the data of another generation, adds Fry. Killewald says it may also be evidence of a longer trend. “The progress towards pay parity has been slower since 1990 than it was between 1980 and 1990, but there has still been progress year by year,” she says. “I think there is cause for optimism.”

And as people – young voters in particular – push issues such as childcare subsidies, tax credits and other policies that would benefit women in the workforce, she says, some of that parity could become more permanent.

“We could think about policies that would, say, reduce the use of mandatory overtime or things like that,” she says, “that would make jobs easier for moms, in particular, to stay in. It's hard to know whether we'll see the same kind of erosion in relative pay for these women as they go through the life course, or if women who were born more recently really have made progress.”