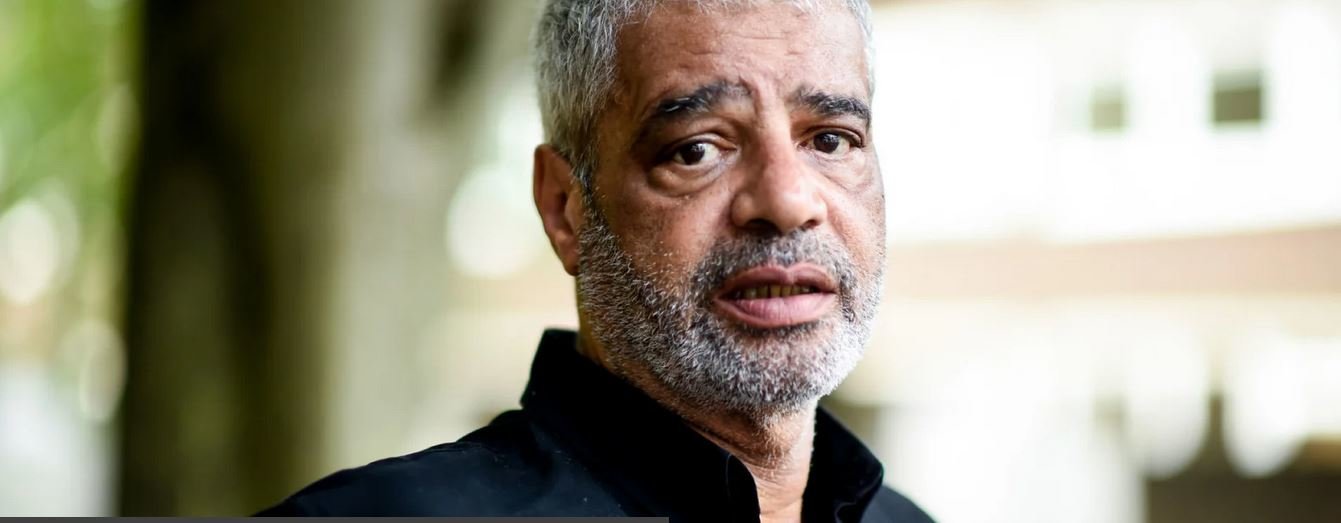

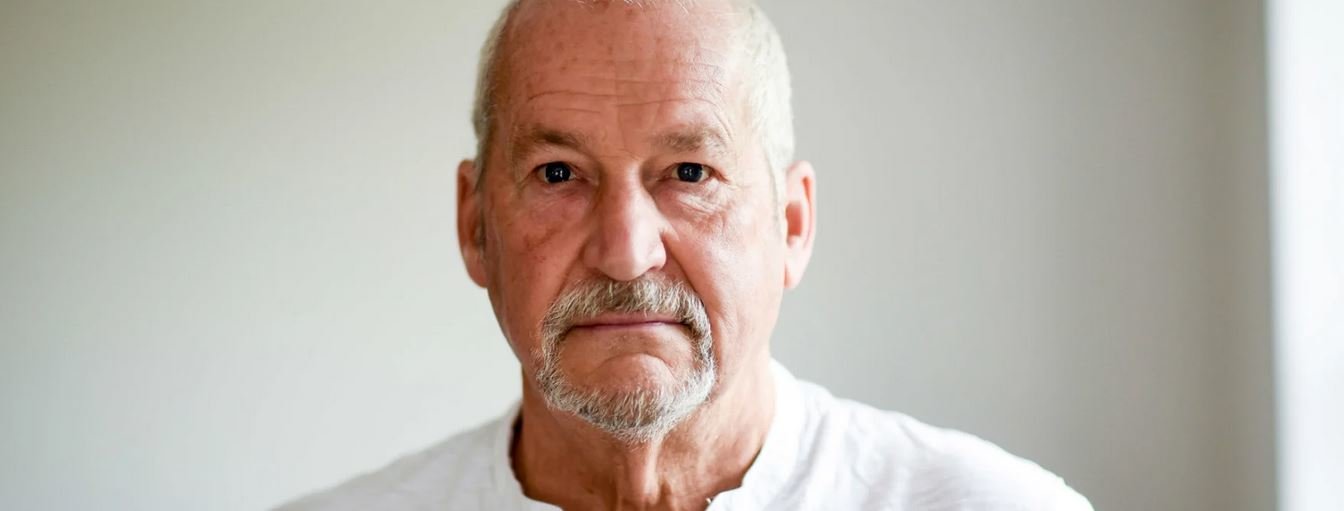

Amadu Darbo says he never spoke of his abuse as a child because “I didn’t have a voice”

Amadu Darbo was five when it became clear his alcoholic mother could no longer look after him. He was put into care in Moss Side, Manchester, then three years later, in 1965, sent to Brookside. More than 100 miles from his home, and without a single relative interested in his well-being, he was isolated.

“I was there for five or six years and nobody came to see me in that time,” he says. “I never went home for the holidays. I was even there on Christmas Day. I was in the middle of nowhere and left on my own with Jack Mount.”

Amadu had not been there long when his head teacher began cornering him in various parts of the school and forcing him into degrading sex acts.

“It happened in the cellar, the changing room, the cottages by the farms, the squash court, the stairs, the big barn... a lot went on in that barn,” he says.

And while he suspected other pupils were being abused, he kept silent.

“We didn’t talk about it among ourselves,” he says. “We were under the impression no-one could help us. I just kept saying to myself, ‘I have to survive, this is not going to be forever’.”

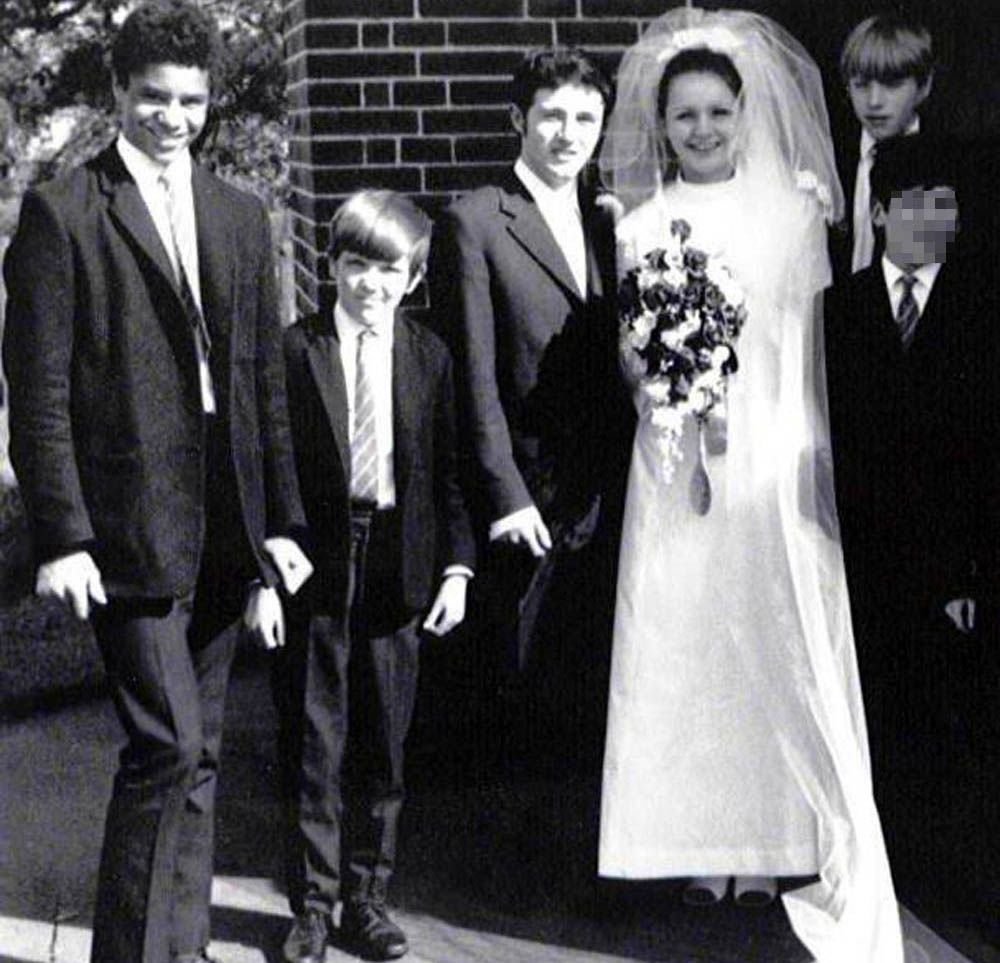

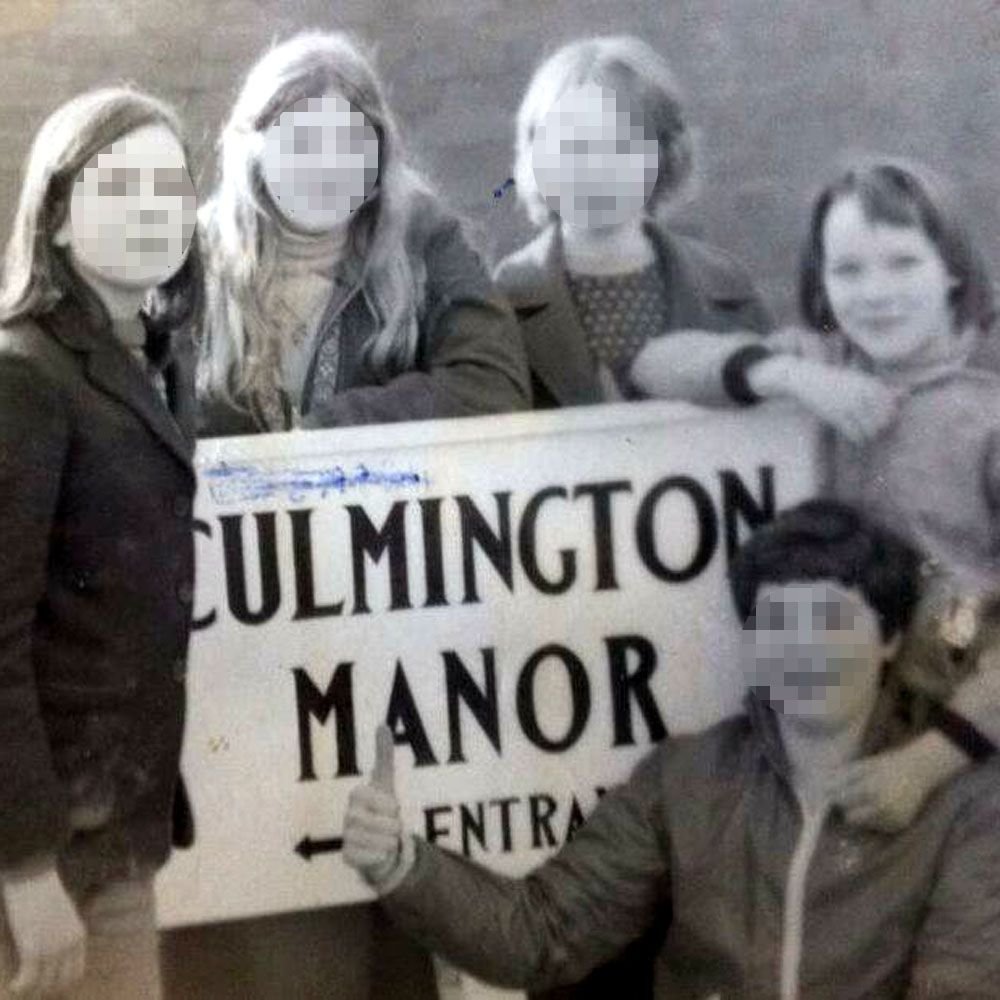

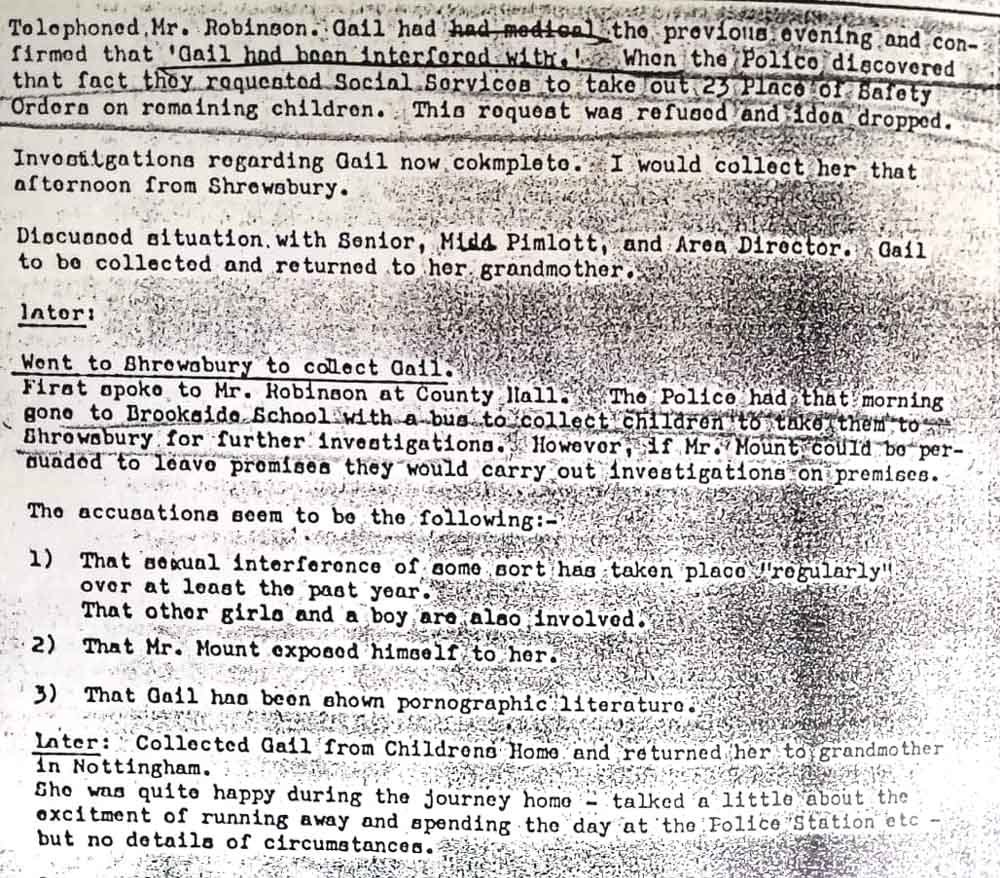

Amadu, far left, Steve Williams, second from left and Philip, back right, were all targeted by Mount

Philip and Amadu ran away time and time again, walking three miles to Craven Arms police station, or if it was shut, trekking another four to Ludlow. But instead of taking their allegations seriously, officers would contact the very person they were trying to escape from.

“They just grabbed hold of my ear and put me in a cell. And then they rang Jack Mount to come and get me,” says Philip.

The beatings afterwards were brutal. One punishment was a lashing with a hosepipe, cut into strips.

“He made us bleed and then he locked us in the blazer cupboard with a plank across the door.”

Boys would flee Brookside and trek three miles to Craven Arms police station

Unable to take any more, Philip’s roommate reported Mount in 1970 to a police officer who believed him. All of the school’s pupils were sent home and officers went around the country interviewing them about the alleged abuse.

“I gave them yes and no answers,” says Philip, now a 64-year-old grandfather. “I just couldn’t say it in front of my parents. They told me the school had been closed and I wouldn’t be going back there.”

Mount was arrested, kept in custody for seven days and charged with 27 offences against 12 boys. The case was sent to Ludlow Magistrates’ Court, but dismissed by a judge who painted him as the victim.

“I would like to express my admiration for [Mr Mount’s] dedication to his calling, his evident sincerity, and the complete lack of bitterness following the tragic experience he underwent at the hand of some of his charges,” the judge said. “I do not doubt his belief in anything he told me in evidence.”

Local authorities paid Mount thousands of pounds to send children to Brookside School

Mount was awarded costs from public funds for his defence and, buoyed by the support, demanded an inquiry into West Mercia Police for wrongful arrest and imprisonment. When it found there had been no wrongdoing, he tried to sue the force.

Meanwhile, he went back to running his school, welcoming a fresh set of pupils. He said 35 children had been taken away by local authorities after his arrest.

“We are hoping that the school will continue and that we can repair the damage done by the police,” he told the Times newspaper. “There are 13,700 children in this country seeking places in special schools, and my concern is there are children who are suffering because they are not allowed to come here.”

It was, Philip believes, a missed opportunity.

“I can’t believe he was able to go back there.”

Maladjusted

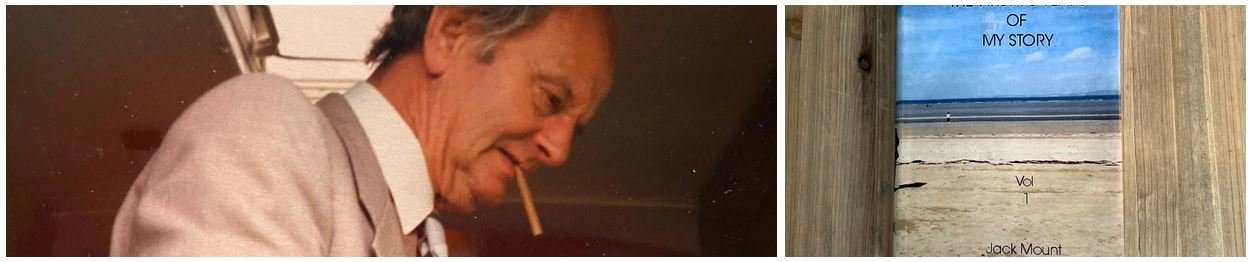

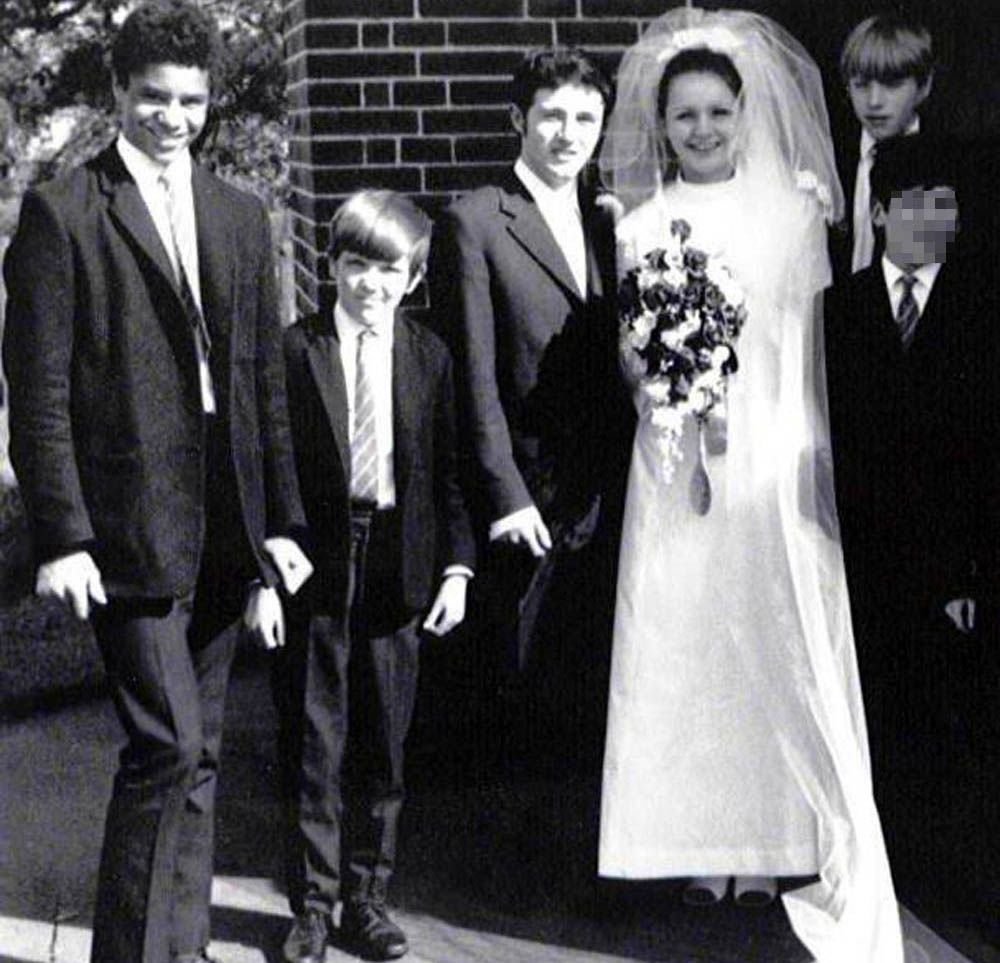

Jack Mount was born in 1919 and grew up around the family farm near Barnsley in South Yorkshire. Living in the countryside with four brothers and three sisters was exhilarating, with days spent building tree-houses and dens, or catching rabbits and moles. In a memoir he wrote about his early life, Mount described the joy of watching Barnsley home games at Oakwell football ground, the smell of hops wafting over from the nearby brewery.

Then as World War Two loomed, a 17-year-old Mount lied about his age to join the Royal Signals. He started as a despatch rider, then became a wireless operator in France and Northern Ireland, where he met his first wife, Beth, before being posted to Italy.

It was clear from his autobiography - self-published to mark his 90th birthday - he enjoyed numerous extra-marital romances while away from home and he censored little about the many women he wooed, even including details of sleeping with a woman in Bologna while his wife was pregnant.

Curiously, he gave a copy to every family member, including Beth whom he had divorced in the early 1960s, and his grandchildren. When they questioned the gall he had in revealing his affairs, he was perplexed.

“He just said, ‘it was a long time ago, what’s wrong with you?’” his daughter Tricia recalls. “He couldn’t understand why we were so upset.”

Mount lied about his age to get into the Royal Signals

Mount, a slim man who was small in stature, left the Army determined to make something of himself and embarked upon a programme of reinvention. He moved Beth, their two sons and two daughters from Northern Ireland to Birmingham, completed a degree in child psychology, and, under the impression it was damaging his intellectual image, replaced his Yorkshire accent with the clipped sounds of an educated English gent.

After completing his teacher training, he worked in schools around Birmingham and became fixated with the idea of opening his own. When Hill House School in Shropshire came up for sale, he seized the opportunity. His new school, which he named Brookside, was opened up to almost every local authority in England and would cater for vulnerable children - or those deemed “maladjusted”. It was, at the time, a term used to describe highly dysfunctional behaviour - but some of the misdemeanors that landed youngsters in Mount’s care were, in fact, relatively minor.

Stephen Hesketh was considered one such child. His mother blamed his “unruly” behaviour on falling off a church roof and badly injuring his head, aged six. He says he doesn’t remember “being that bad as a kid”, but in 1968, he was taken from Liverpool to Brookside.

“My mum said to me, ‘if you don’t like it, just tell me and we’ll go’. I looked around and it seemed to me that the kids weren’t happy. I walked into a hall with big windows and I turned to my mum to say I didn’t want to stay.”

The last thing nine-year-old Stephen recalls seeing out of those windows was his mother driving away: “She just jumped in the car and left. I’ve never known whether to blame her or Mr Mount.”

Stephen was adopted by an American army captain in 1974 and has lived in the US ever since

Stephen’s abuse began in much the same way as the others - while doing chores in the barn. He had gone to get hay when he heard his head teacher’s voice in the darkness.

“He asked another boy, ‘do you think he would do this?’ I ended up doing things I didn’t like. If you did, you got to have the horses and chickens. There were a lot of plusses to doing what he wanted you to do.”

He ran away three times - first to the police station, then by jumping on trains to Manchester and Liverpool. Every single time, Mount was called to take him back to Brookside.

“I thought, if I get home, mum will get the police, but she did not get the police, she called Mr Mount,” says Stephen, who later moved to Nevada when he was adopted by a US army captain. “I’d be in the back of the car knowing what was going to happen to me - he’d put me in the blazer room [and keep] me there for three to four days, maybe a week.”

On one occasion he was whipped with a bridle as punishment and passed out from the pain.

“For years I had nightmares.”

Both Stephen Hesketh and Steve Williams were approached while doing chores in the barn

One boy repeatedly fought off Mount’s advances and was regularly thrown in the blazer cupboard for his disobedience.

“The window had been nailed shut, but we learned we could get out if we lifted the floorboards and crawled under the door,” says Steve Williams, who later channelled his anger about how he had been treated into teaching martial arts.

“I ran away every chance I got. I made it clear that if Mount touched me I’d scream.”

Despite this, Mount persisted. On one occasion in the barn, he encouraged Steve to look at a pornographic magazine while performing a sex act in front of him. When the young boy refused to participate, he was knocked unconscious and awoke to find his headmaster abusing him. Later that night, Mount approached Steve in his dorm room - when he pretended to be asleep, he saw Mount assault a boy in a nearby bed.

“I can say that I saw what happened with my own eyes and he was 100% guilty.”

Mount’s second wife, Elizabeth, worked at Brookside and was known as “matron” to pupils

By 1974, police had been informed of more allegations against Mount. He went on trial in the December at Shrewsbury Crown Court, charged with indecent assault, attempted gross indecency, and incitement to commit gross indecency.

Records from the period are believed to have been destroyed due to the passage of time, but it is understood he was found not guilty of one charge and a retrial was ordered on the others. He was tried again at Stoke Crown Court two months later, in early 1975, but was cleared.

For the third time, he was free to return to Brookside, where he picked up the mantle of head teacher once more. This time, he opened up the school to girls.

Escape

Gail Marshall had a difficult start in life. Her dad was in prison,

her mum had abandoned her, and she was put in care from the age of two.

She spent years in a string of local authority children’s homes and

boarding schools in Leeds and Nottingham. Her life became no easier when

she was sent to Brookside by Nottinghamshire County Council, aged eight

or nine.

“I remember them saying I was maladjusted. I used to

think, ‘maladjusted - what does that even mean?’ To this day, I don’t

know why I was sent there. I think they were trying to find places to

put up with me.”

Gail remembers many of the staff fondly and says the school seemed like a nice place in the beginning

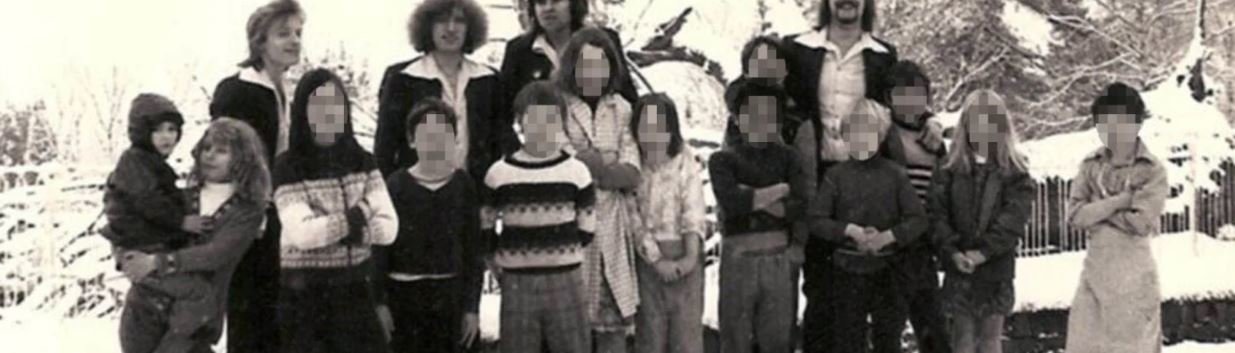

There

were about 15 pupils at the school when Gail joined in 1975, not long

after Mount’s trial. Several members of his family worked there,

including his daughter, Tricia.

“There were animals, a swimming

pool and all the staff were friendly,” Gail recalls. “If it wasn’t for

what happened to us, it would have been a nice place.”

Mount wasted no time in making regular trips to Gail’s dormitory at night.

“He’d

come in, ask if you were all right. And then he’d put his hand up your

nightie. Jack Mount came across as a nice guy. Now I know that [was] his

way of getting to you.”

Marina Musker, who arrived a year later in 1976, says Mount became increasingly brazen.

“He’d

come in and carry the girls out of the dorm - we’d all be there

wondering who he’d pick tonight. Sometimes he’d take more than one, that

was when we knew he was getting greedy.”

Mount seemingly became

more emboldened as time went on, carrying out attacks in more public

places, where staff members could stumble upon him.

“He sat me on

the wall in the greenhouse and had sex with me,” says Gail. “And then

the gardener walked in and he quickly pulled away.”

On another occasion, in the school hall, he raped a fellow pupil and forced Gail to watch.

“Maybe I thought it was normal. All my life, I’d been battered and abused - I had no idea what was right or wrong.”

Marina Musker, leaning on the sign at far right, was beaten by Mount on several occasions

Marina felt similarly confused - initially mistaking Mount’s interest in her for kindness.

“That

was the first place he got me,” she says of an attack at the chicken

coop as she collected eggs. “I think in some ways, I was pleased he was

paying me attention. I knew it was wrong, but he properly groomed me. He

abused me most days.”

Being allowed to leave Brookside for the

holidays was a privilege to be earned and Marina was never allowed to

return home to Merseyside - she presumes because Mount suspected she

might tell her family the truth. When she tried to tell her father on

the phone instead, she heard a click on the line. Almost as soon as she

hung up, Mount appeared and beat her black and blue.

“I got

jumped all over. The pain in my ribs and my arms was horrific. After

that, I was watched constantly because they knew I’d want to run away.”

Marina Musker was taken to Brookside by staff from Sefton Education Authority - she thought she was going for a day out

There

was no hiding what had happened to Marina. A member of staff, already

suspicious at what was going on at the school, was shocked when she saw

the state of her.

Jean Tantrum did cleaning and odd jobs at

Brookside - a mother herself, she doted on the girls, and they were just

as fond of her. She wrote down her phone number on a piece of paper and

gave it to Marina and Gail.

“She said, ‘if you ever need me, give me a call’ . She didn’t say so, but she must have known what was going on,” says Gail.

Marina and Gail credit Jean Tantrum with saving them

It

was in the dreaded blazer cupboard that Marina heard Gail sobbing in

the bathroom next door and the pair made their escape plan: “I shouted

to her, ‘we are getting out of here’.”

They fled as soon as they

could, running through the woods to the main road where they called Mrs

Tantrum from a phone box. Hours later, they were examined at the police

station.

“I just remember them saying ‘her hymen’s broken’. I didn’t know what a hymen was,” says Gail.

Jean died last year aged 89. Her family described her as a “person of principle” who would want to put right any wrong she saw.

“She always believed the girls,” her daughter says. “She said they could not have made it up.”

“Thanks to Mrs Tantrum we never went back to the house of horror,” says Gail.

The

girls’ accounts led to Mount being charged in 1979 - for the third time

in 10 years. It should have marked the end of their ordeal, but in some

ways it was just the beginning.

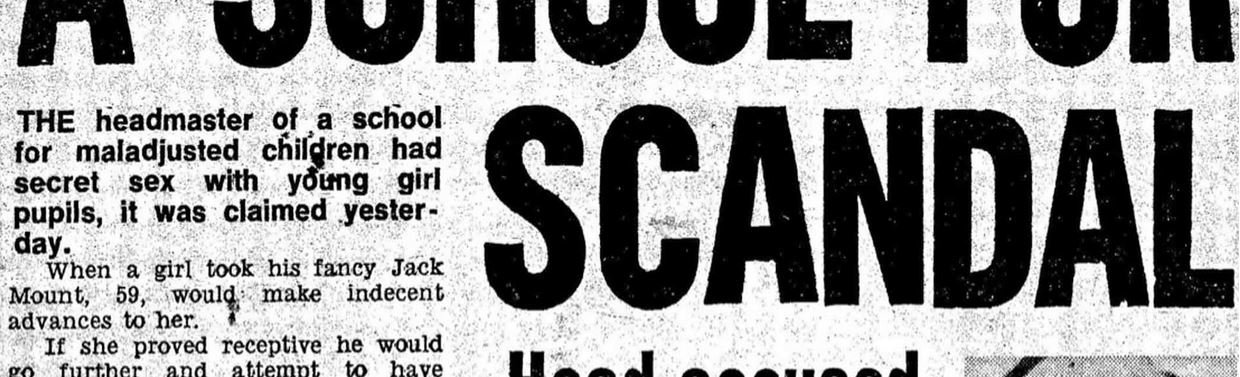

The case was high profile and made newspaper headlines that make for shocking reading by today’s standards

The charges involved offences

against six girls, including sexual intercourse with a female under 13, a

female under 16 and indecent assault. But for reasons they do not know,

Gail and Marina were never asked to give evidence in the trial at

Stafford Crown Court.

“We had told police exactly what was going on. Why weren’t we included? The evidence was there,” says Gail.

The

case was high profile and made newspaper headlines that make for

shocking reading by today’s standards. “Gymslip girls tell of school

orgies”, one report in the Sun stated, while others referred to the

girls as being part of Mount’s “love squad”, up for “three-in-a-bed sex

sessions”.

The court heard victims were as young as eight but

they were portrayed as willing participants and “obsessed with sex” by

the defence.

The prosecution’s argument was not dissimilar:

“There is no doubt some girls positively enjoyed what was going on. But

these girls have to be protected whether they like it or not.”

Children said the abuse took place all over the school grounds

After

hearing the girls’ evidence, Justice Stephen Brown ruled they had made

up the allegations. He directed the jury of seven men and five women to

find the head teacher not guilty.

Afterwards, a relieved Mount maintained his innocence.

“Now

I hope the police will believe me. The allegations were disgusting and

ridiculous,” he told reporters, vowing to once again take legal action

against West Mercia Police. “It’s been one long nightmare for me and my

family.”

This time, though, Jack Mount closed the school. It never reopened.

Tricia says growing up with Mount as a father was like “being under his spell”

Tricia

Tricia

Mount recalls a somewhat happy childhood, albeit one that was

controlled by her strict and authoritarian father. She had just turned

11 when she says he began visiting her bedroom once her brothers and

sister were asleep.

“He never said anything,” she says. “He

would stand by the bed, take my hand and make me do things to him. When I

could hear him coming upstairs, I’d just have this feeling of dread. I

remember thinking, ‘if I say anything, my life will be destroyed’. So I

buried it.”

Being abused by the father she loved and trusted left her extremely conflicted and confused.

“It

just couldn’t be wrong because he was my father,” she says she

reasoned. “I can remember trying to think to myself… ‘what was it all

about? Maybe fathers do this, prepare you for adult life?’ I was trying

to justify it.”

Tricia was a child when her father began abusing her

Tricia

says she was abused on several occasions in the early 1960s, but does

not recall it happening beyond the age of about 12. She tried to forget

what he had done but remained under his control, much like the rest of

the family. Even after divorcing Tricia’s mother, Mount kept Beth close,

controlling her finances for the rest of her life and inviting her and

their children to family gatherings with his second wife, Elizabeth.

“He

was very much the boss in our house,” says Tricia. “He had such a hold

over people psychologically. He was so powerful. You just didn’t say

things against him.”

When she was older and her father suggested

she worked at Brookside, Tricia agreed, becoming one of several family

members he employed. It was, she now believes, one of the ways he

managed to hide his wrongdoing - by hiring people he already wielded

power over.

Tricia doesn’t remember the abuse happening beyond the age of about 12

She

maintains she was stunned when the first allegations emerged in the

early 1970s about her father molesting boys. She says she had never seen

or suspected a thing, despite her own traumatic experience.

“I

was shocked. I didn’t believe it. I just couldn’t connect it all,” she

says. “It was so different from what he’d done to me [because they were

boys].”

Like the rest of the Mount family, Tricia felt compelled

to support her father during the early court cases. Only when the school

began to accept girls were her suspicions raised, particularly when she

saw him with a child he wasn’t supposed to be with. But the terror she

felt at revealing anything about her own abuse forced her to remain

silent.

Only 30 years later, when her father was much older and

his power over her had waned, did Tricia feel able to tell her

relatives, who believed her, to her relief. Then in 2012, she went to

Ludlow Police Station - the place where so many children’s reports had

fallen on deaf ears 50 years before - and reported her 93-year-old

father.

As a young adult, Tricia worked at the school

The

fact it took Tricia several decades to feel able to speak out is

typical of victims of non-recent abuse, says Julie Taylor, professor of

child protection at the University of Birmingham.

“It’s very,

very common - it’s why people get away with it,” she says. “They have

this coercive control and power over their victims - ‘I’ve given you a

job, I’ve brought you up OK - you’re not going to speak out now’.

“In some interactions with her father as an adult, Tricia will have still felt like a child.”

The

guilt of not saying anything sooner has tormented Tricia for years. The

mother of two believes she could have prevented pupils becoming

victims.

“I regret it so much. I was groomed from an early age,”

she explains. “I feel dreadfully awful. I feel [the children] wouldn’t

have gone through it if I’d have said something.”

Former police officer Gene Edwards spent years investigating Jack Mount

‘Yewtree Effect’

Gene

Edwards first heard the name Jack Mount in 1999, when he was tasked

with interviewing ex-Brookside pupils whose names had come up during one

of Greater Manchester’s largest ever child abuse investigations. More

than 200 men had claimed they had been molested in the city council’s

care during the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s - and several said the abuse

continued when they were sent to Shropshire.

When their names

were passed to West Mercia Police, it was to Gene they again recounted

their stories. The details were strikingly similar: the locations of the

attacks, the way Mount used fellow victims to entice new ones, the

beatings and the blazer cupboard.

Seven former pupils were

willing to testify against Mount, who was by then 79. But when the

evidence was sent to the Crown Prosecution Service, it concluded “there

was insufficient evidence to provide a realistic prospect of conviction

for any offences” and the case was again closed. Some of the witnesses

were furious at the decision - and at Gene.

“I had to get back in

touch with all these people and tell them it was going nowhere,” he

says. “It’s one of my worst nightmares, delivering information like that

- I was gutted for them.”

The watershed moment in the treatment of victims of non-recent abuse would not come until 13 years later.

In

2012, Jimmy Savile’s prolific sex abuse against children - and the

failure of various organisations, including the BBC, to tackle it - came

to light. The subsequent police investigation, Operation Yewtree, saw

several high-profile people convicted, including Rolf Harris, Gary

Glitter and Max Clifford.

Police forces around England reported a

surge in complaints about non-recent child abuse from victims buoyed by

the bravery of those prepared to speak. It was the “Yewtree effect”

that spurred Tricia on to report her father the same year. But again,

prosecutors did not believe there was a realistic chance of conviction.

“They said there was no corroborating evidence,” she says. “I thought it was all over.”

The children of Mount’s first marriage disowned him after learning of Tricia’s abuse

The

rumours surrounding Mount, however, persisted. Ex-pupils began posting

about their abuse on a

Facebook page dedicated to the school. Claims of

mistreatment were discovered on blogs. It prompted West Mercia Police to

begin building its biggest case against Mount.

Gene had retired

as a constable but was working as a civilian officer when he and Det Con

Gavin Smith began speaking to former pupils all over the country, many

of whom were understandably distraught.

“We knocked on the door of a 50-year-old truck driver. He just broke down and said ‘I know why you’re here’,” says Gavin.

Among

those willing to speak were Philip, Amadu, Gail and Marina. But there

were countless others who had never met each other, and who had attended

the school sometimes years apart, whose accounts of what happened

repeated the same details.

“It is my belief that they were

telling the truth, it was their mannerisms and the modus operandi - it

was so, so similar in every story,” says Gene.

Gavin adds: “We’d come out and look at each other and just say ‘Jesus - how did [Mount] get away with it?’”

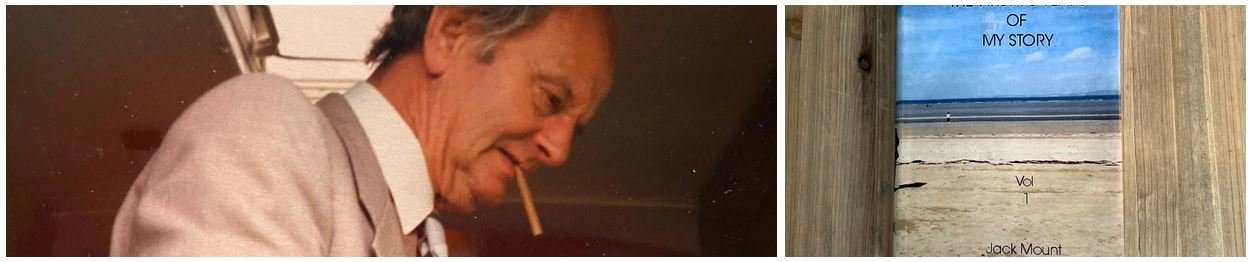

Gavin Smith believed Mount “painted himself to be the victim”

They

found 19 people they could put forward in the case against Mount,

including Tricia. Officers went to his home in south Devon and took him

to be questioned at a police station, where Gavin was initially

surprised at the old man’s energy.

“He came across as this

sprightly, elderly man, you’d never have thought he was in his 90s. But

as soon as he was interviewed, he completely changed. He was very

manipulative.”

Mount, who suddenly seemed feeble and forgetful, denied every single allegation put to him.

“He would not concede to any of it. He said he couldn’t remember victims’ names and denied everything,” says Gavin.

“He

even chastised them - he said it was a conspiracy. To make it up would

have had to have been a conspiracy of massive proportions. I never

doubted what these people were saying. It was identical.”

This

time, the Crown Prosecution Service charged Mount with 50 sex abuse

offences against children. His trial was scheduled at Barnstaple Crown

Court, near his home, due to his age.

At 96, he was the oldest person ever to face historical sex abuse charges in a British court.

Mount, who appeared frail in the dock, was accompanied to court by his wife

Control

The

sight of Jack Mount in court was a pitiful one. He shuffled in on the

arm of his wife, and apparently needed a carer to help him to his seat

and explain what was being said. He appeared a doddery, confused old man

- the same one police encountered in the interview room when the tape

began recording.

Hours of legal argument before the trial

discussed how such an elderly defendant, who by now had been diagnosed

with Parkinson’s disease, would cope with evidence from 19 alleged

victims.

Judge Geoffrey Mercer ruled the case would be split into

three trials to make the process more manageable for Mount. It was a

crushing blow - no single jury would hear from every single witness,

dramatically reducing the overall weight of evidence.

For the

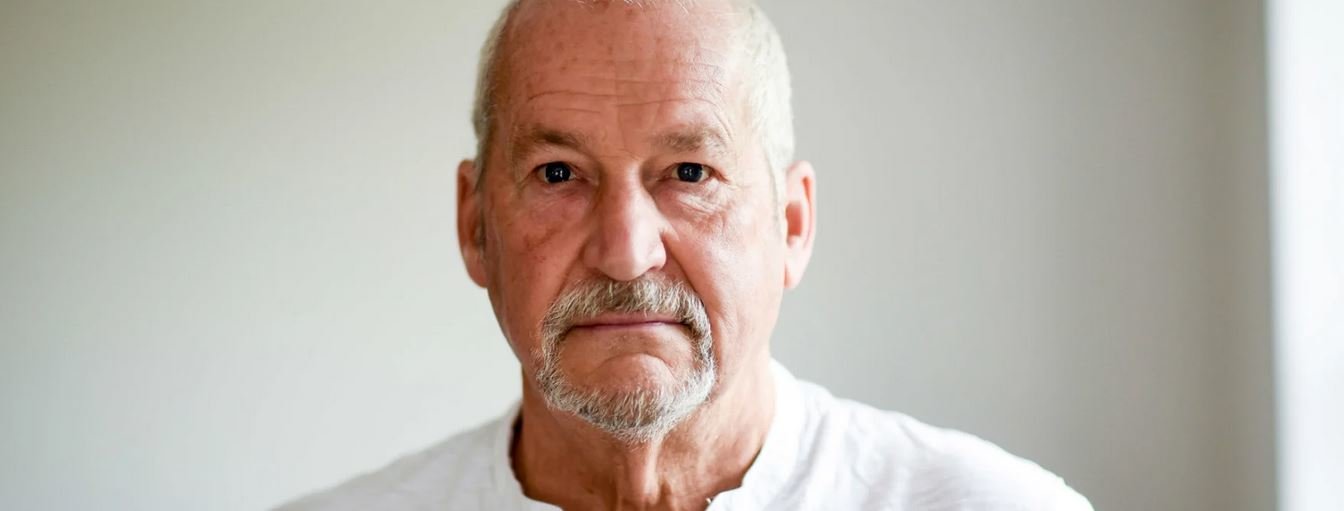

second time, Gail and Marina were told they would not be able to give

evidence - this time because statements they had made in the 1970s could

not be traced, despite Gail’s social care records confirming she had

been “interfered with”.

“I just broke down,” she recalls. “I proper sobbed. I’d wanted to look him right in the face and tell him what he did to me.”

Gail’s social care records referenced that she had been “interfered with”

For

three days, Tricia’s life was pored over. Letters she had written to

her father over many years were scrutinised, the contents of her diaries

laid bare. Family photographs, including one of them smiling together

at her graduation, were shown to jurors. The defence argued the evidence

showed mutual love and affection.

“I was absolutely torn apart -

I was thrown to the wolves,” says Tricia, now 69. “I told the court I

loved, respected and trusted [my father] - which was true, at that time.

But I’d been groomed from an early age. It felt like it was me on

trial, not Jack.”

Tricia believes her father thought he had “rescued” vulnerable children

When

Mount took the stand, he coughed repeatedly throughout his evidence,

telling the court Parkinson’s had affected his speech. While he was in

the dock, Tricia felt her father was in charge of her life again.

“It

made me feel sick, to imagine him there, portraying himself as the

loving father who can’t understand why the daughter he did so much for

had turned on him. I couldn’t believe the jury would be able to see

through all that. He’d be so convincing.”

Tricia’s intuition was, devastatingly, spot on. It took the jury three days to find Mount not guilty of abusing his daughter.

“I

was distraught. Why did the judge decide to split the trial? That is

what destroyed it for me. If we’d all been able to go in together and

face a jury... nobody could have given an acquittal on that.”

The cases were heard at the courthouse in Barnstaple

Six

months later, the second trial began. It involved four complainants,

including Amadu, who by then had spent more than 20 years as a social

worker helping vulnerable children. He didn’t believe Mount’s claims of

fragility, which had convinced the court to sit for just two 30-minute

sessions a day.

“I knew he remembered. He had his eyes closed. I

thought... look at me. I have an Armani suit, a nice house, money in the

bank. And I haven’t gone away. The power was with me, I felt sorry for

him.”

The jury returned not guilty verdicts on three charges, but could not reach a decision on five others.

Amadu was a social worker for 23 years, helping children who found themselves in the same situations he did as a child

The

CPS requested a retrial, but Judge Mercer, who has since died, ruled

Mount was too frail to face further legal proceedings. Not only would

there not be a retrial, but the third trial would not take place at all:

Mount was again in the clear.

“All this time, all this

information, and all these people who had been hurt - and the

establishment were still questioning us,” says Amadu.

“They made me feel like I wasn’t worth it [back] then, and I wasn’t worth it now. He got away with it again and again.”

Jack Mount lived another three years. He died, aged 100, on 25 June 2019.

His

son by his second marriage rejected all the allegations made against

his father. He did not want to add anything to this article on his

behalf.

Mount’s school in the Shropshire countryside was the focus of several trials

Failing to pin anything on Mount is one of the biggest disappointments of his 30-year career, says Gene, who has since retired.

“Over

that time I saw a lot but the Jack Mount case hit hard because we

failed so miserably at it - it should have been dealt with a long time

ago.”

Gavin spoke to between 30 and 50 victims on the case, many

of whom did not want to give evidence. The detective believes there are

many more victims than the ones he and Gene were able to trace.

“I

never expected it to be so big. Mount is certainly up there among the

worst paedophiles in this country - I would expect there to be 60 to 100

victims.”

Philip had been due to give evidence in the third trial. Hearing Mount would never face legal proceedings again was shattering.

“I

was gutted I didn’t get my chance to have my say - we were pushed back

into a corner like we were children again. Mount knew how to play it, he

got what he wanted. What he did was on a Jimmy Savile-scale.”

Marina, who has a son and daughter, has praised all those who have spoken out

For

Marina, telling her story now is some consolation for being denied her

chance to speak in court. She has been traumatised by what happened and

has to sleep with the television and lights on.

“The school was a hellhole of abuse, Mount should have gone to prison. We were abused - it happened.”

But she hopes that coming forward will encourage other victims of Mount to do the same.

“I want to tell them I understand and I know how difficult their lives will have been… [that] they are so brave.”

Philip has been back to the school grounds on a number of occasions to try to come to terms with what happened

Gail

received some acknowledgement of what happened to her: in 2016, she was

awarded £10,000 by the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority. Her

care records had shown social services in Leeds warned Nottinghamshire

County Council not to send her to Brookside, owing to the many

allegations made about Mount in the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

It

was, however, cold comfort for the mum of four, who has struggled with

her mental health, been in trouble with the police and suffered violent

relationships. But she has found hope in her eight grandchildren.

“When I look at the bigger picture, now, I look at my life, and I think it wasn’t my fault. I was just a kid.”

Though

it can never undo what he went through, Philip feels a weight has been

lifted since deciding to waive his anonymity and tell his story.

“I’m

glad I can now be heard and that people will know what a monster he

was,” he says. “The police would not listen back then, and the system

would not listen - but I survived him.”