Protests aimed at toppling autocratic leader have been led by women and show no sign of slowing

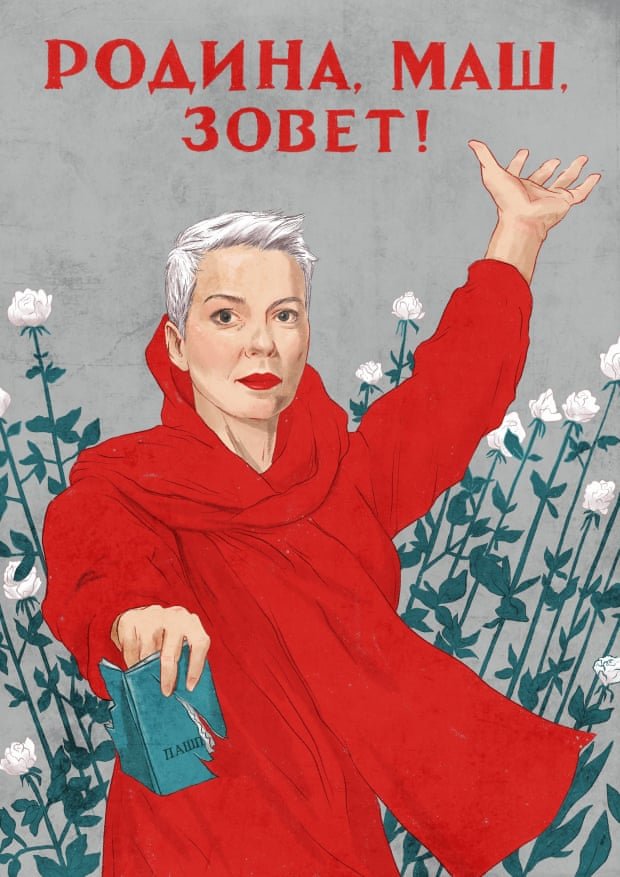

One evening last week, a stylised image of the Belarusian opposition leader, Maria Kolesnikova, was projected on to the wall of a Minsk apartment block.

Mocked up to look like the famous Soviet war poster The Motherland Calls, the image created by Anna Redko shows Kolesnikova heroically holding out a torn passport – a reference to her actions on the border with Ukraine on Tuesday when Alexander Lukashenko’s security services tried to deport her.

“She decided on a powerful gesture. That’s why she is one of the opposition’s leaders and I’m the press secretary,” Ivan Kravtsov, one of two others with Kolesnikova who did get deported, told journalists in Kyiv the next day.

Kolesnikova is now in a KGB prison in Minsk, and her determination not to be forced into exile was the latest impressive act of defiance in a revolutionary moment that has, from the beginning, been led and defined by women. On Saturday afternoon, women holding flowers and posters gathered in Minsk to protest – some were detained by masked men in green uniforms. The Saturday demonstrations have become a regular occurrence before the main Sunday protest in the city centre, , where for the past four weekends, more than 100,000 people have assembled.

It was a female candidate who rallied support against Lukashenko before last month’s elections. The autocratic leader had jailed or exiled the men who wanted to stand against him, but thinking a woman could not pose a real challenge, he allowed the wife of one of his opponents, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, on to the ballot. Along with Kolesnikova and Veronika Tsepkalo, the wife of another candidate who fled Belarus after receiving threats, the three women travelled the country and won support for their simple message of facilitating political change.

Lukashenko’s misogynist rhetoric also served as a mobilising force. “The cynicism with which the current president expressed himself about them and their role, it insulted a lot of women,” said Kolesnikova in an interview at her campaign headquarters in central Minsk last month.

It was also women who provided the momentum for the protest movement’s rejuvenation after the horrific violence inflicted on demonstrators in the aftermath of Lukashenko declaring an implausible victory.

After three evenings of brutality from riot police, 250 women, dressed in white and holding flowers, stood defiantly on a roadside in central Minsk. Police left them untouched and the next day there were multiple rows of flower-waving women throughout the city.

In recent weeks, as most of its leaders have been forced out of Belarus, Kolesnikova has become the visible face of the movement, appearing fearless and cheerful despite the odds stacked against the protesters, regularly appearing at rallies until her kidnap-style arrest earlier this week.

Last month she said her role had been simply to show people that it was possible to demand political change. She said: “The west, Russia won’t help – we can only help ourselves. In this way it turned out that female faces became a signal for women, and men too, that every person should take responsibility.”